Early America

Upton’s Hill looks out over the valley of Four Mile Run. In the early years of the republic, the waterway provided all who lived there with a critical mode of transportation from the Potomac River to the headwaters of the run.

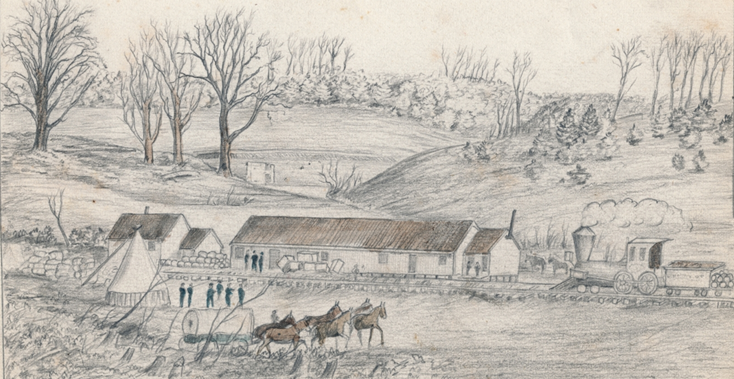

As America expanded, transportation spread from the coastal waterways to the mountains west. In 1860, the Alexandria, Loudoun & amp; Hampshire Railroad was established. It linked Alexandria City with Leesburg, and its route ran along the valley of Four Mile Run as it gradually climbed out of the Potomac Basin. Trains wound their way around the base of Upton’s Hill.

Upton’s Hill is named after Charles H. Upton (1812-1877), who was from Massachusetts and built a home on the hill in 1836. He farmed and engaged in literary pursuits. He held several local offices before being elected to Congress in a special election in May 1861.

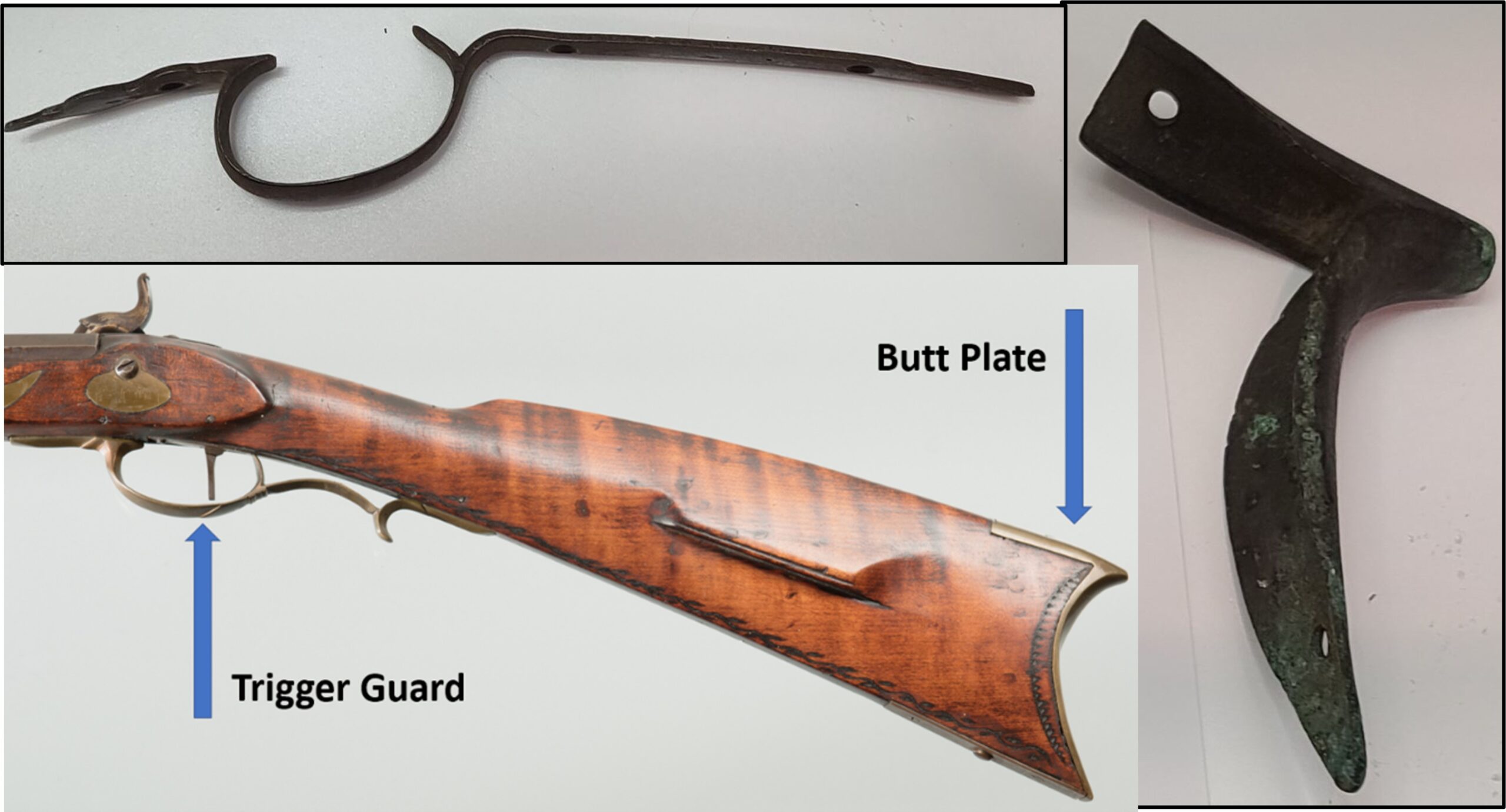

Buried deep in the first layer of Upton’s Hill history at the Arlington Historical Museum are artifacts that date to the era between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. The metal parts of weapons have been identified as elements of guns that predate the Civil War. However, soldiers often brought weapons from home to use in battle.

As the Civil War erupted, Charles Upton sent his family to safety in Washington, D.C. He successfully ran for Congress as a Unionist in a special May 1861 contest representing Alexandria County (now Arlington). His term lasted only nine months because Virginia seceded from the Union, and no representative could be seated in the US Congress. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Upton to be US Diplomatic Consul to Switzerland by President Lincoln, and he served in that post for 14 years until he died in Geneva. He is interred at Congressional Cemetery.

Trigger and hammer from a rifle.

Trigger guard and butt plate for a long rifle (c. 1700-1850) shown with an annotated image of the rifle of the early 1800s to show location on the weapon.

The Febreys and the Civil War

John E. Febrey (1831-1893) and his wife, Mary Frances Ball (1835-1914), bought Upton Hill property around 1850 and built two homes. One was built around 1865, and the gray-shingled house was expanded under subsequent owners but demolished in 2021. The other was a wood frame house across what is now McKinley Road that was demolished in 1966. The Febreys improved the land and farmed corn, oats, rye, buckwheat, and barley. John also added barns and a chicken coop.

John’s brother described John’s 138 acres as “a fine flourishing farm, with a fine dwelling house, a large barn, on 100-by-150 feet, with outhouses and a stable.” John’s property included a water business at Powatan Springs, a freshwater spring near the current Dominion Hills Pool, where the water was bottled and delivered to buyers in D.C. In the 1890s, John Febrey was the superintendent of Alexandria County (now Arlington) public schools. He died in 1893

During the early months of the Civil War, Confederate and Union troops vied for control of the hill, which offered a view of Washington and command of the surrounding area. Confederate troops first occupied the hill after the disastrous Union defeat during the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861. Union troops took it back in September of that same year.

According to records of the congressionally chartered Southern Claims Commission, Febrey, who sided with the Union during the war, applied for compensation from the federal government for the livestock and crops taken by Union troops. Testimony in those records helps to tell the story of Upton’s Hill. In the spring of 1861, Confederates pulled down Febrey’s smaller house for wood to make a signal station. General J. E. B. Stuart’s troops fired shells as they rode through, and Febrey fled to the home of his in-laws, the Shreve family, in Falls Church. Union troops took possession of the Upton’s Hill area in September 1861 under General James Wadsworth after the second battle of Bull Run. Febrey testified that Union troops picked and ate all of his 15,000 head of cabbage. Records show that Febrey sought $7,720 for confiscated timber, buckwheat, com, cattle, and fencing and that he got some of that money back.

Upton’s Hill in the Civil War

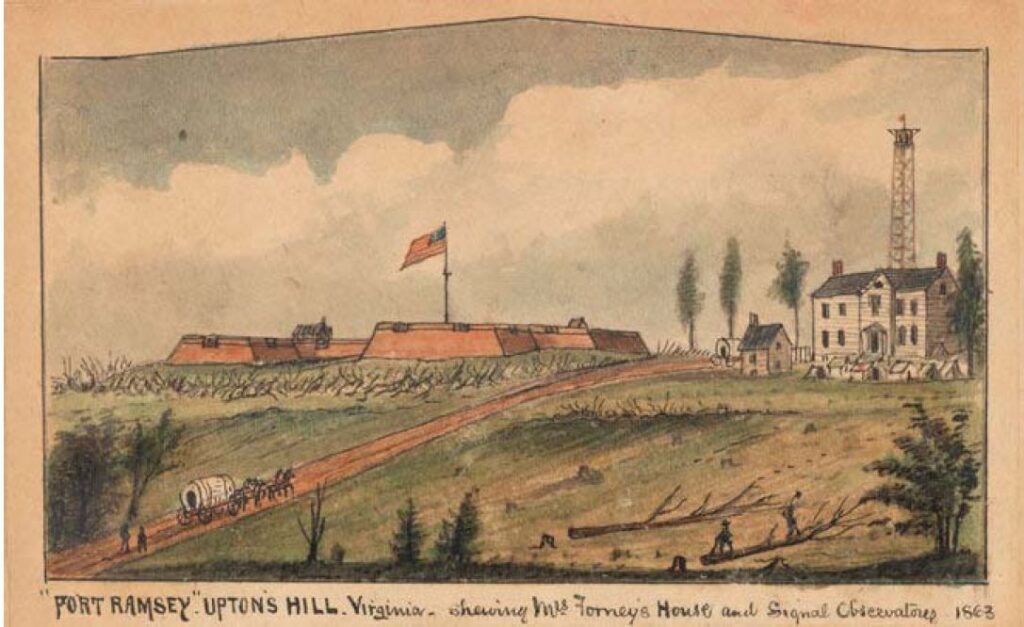

Union troops used Febrey’s home as its headquarters. They built a large masonry fort at the crest of the hill and initially calling Fort Upton but later renaming it Fort Ramsay.

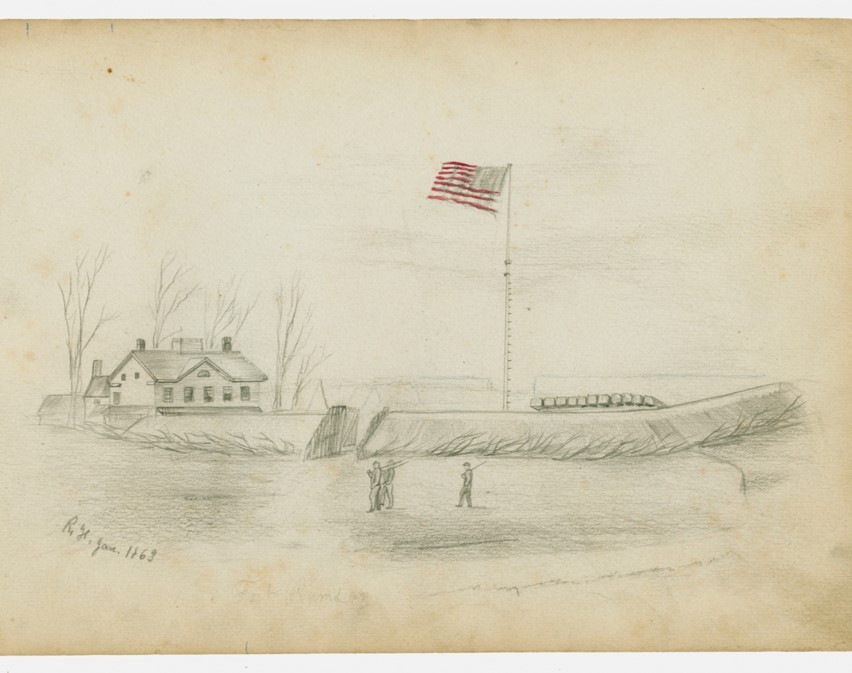

Artist Richard Holland’s depiction of the fort on Upton’s Hill, 1863

Soldier and artist Robert Knox Sneden’s depiction of Fort Ramsay at Upton’s Hill, 1863, looking at the base of Upton’s Hill looking north.

By the end of the war the Union had built a tall wooden observation tower atop the house which provided line-of-sight communication with other observation and signal stations and the Washington Monument. The site became a logistics center for the region’s Union troops linked by railroads as seen in this 1863 sketch of the Union railroad depot (below).

Julia Ward Howe wrote the words to the Battle Hymn of the Republic, after she witnessed a review of the troops in November 1861. She was inspired by the sights and sounds of the day, campfires on Upton’s Hill, and men singing the popular tune John Brown’s Body Lies Moldering in the Grave. After the Civil War the fort was abandoned. But the railroad continued to serve the community that grew nearby.

The view from the top of Upton’s HiIl looking down toward Four Mile Run on tents of the 1st Ohio Volunteer Regiment, June 17, 1861. Artist: Alfred R. Waud

Metal curtain rings. Curtains were often used at the entrance of a large tent or an officer’s quarters.

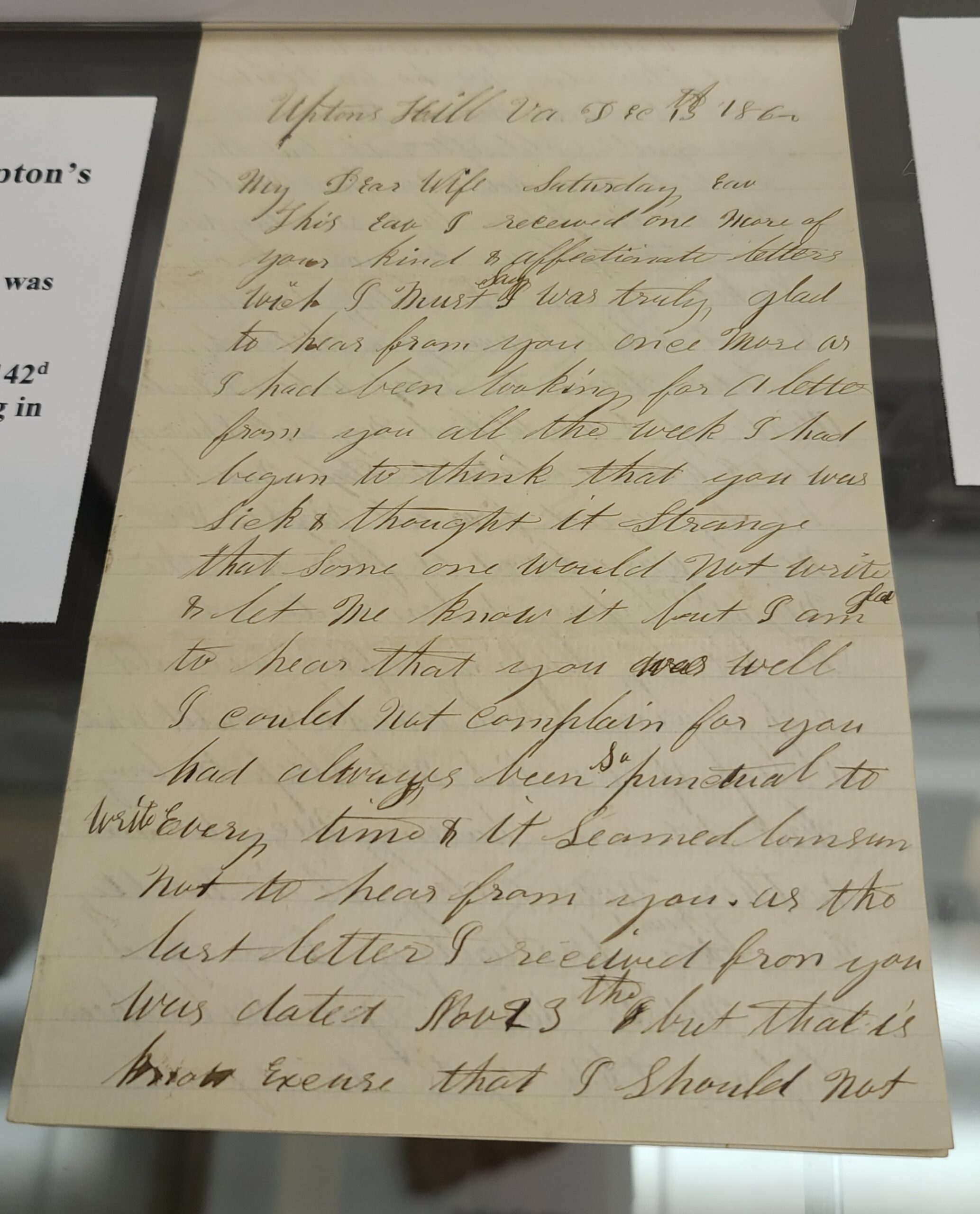

Letter written by Erastus Stacey from Upton’s Hill to his wife on December 13, 1862. Stacey was 27 years old. He enlisted in August 1862 in DeKalb, New York as a corporal. He was killed in battle in Virginia in 1863.

Transcription of Erastus Stacey’s letter:

Uptons Hill VA Dec 13th 1862

My Dear wife Saturday eve

This eve I received one more of your kind affectionate letters which I must say was truly glad to hear from you once more as I had been looking for a letter from you all the week. I had begun to think that you was sick and thought it strange that someone would not write and let me know it but I am glad to hear that you was well. I could not complain for you had always been so punctual to write everytime and it seamed lonesum not to hear from you. As the last letter I received from you was dated Nov 13th but that is not excuse that I should not have written before. One week ago last Thursday we was visited with a snow storm and it was quite cold after it but the snow is gone now and we have mud now in its place. Last Sunday we had the pleasure to go out on Picket again. The only trouble I had while I was gone that when I laid down to sleep when I would wake up I would find myself shivering but I was not aloud to sleep much. We kept a good fire all night. We never was allowed a fire in the night before when out on picket, by keeping a fire we could keep warm when awake and could when a sleep if we did not sleep to long but we are having nice warm weather now only it is windy. We heard yesterday some good war news which you will hear before this gets to you. We are all anxious to go and help the boys that are doing the fighting but we shall have to wait until we get better drilled but we are ready to go any time when they call on us to go. The health of the Regt is good now. Most of the boys that has been sick is getting well again. We have had only one death in the Regt. It was a young man from Helvetian NY the name of Smithers. His father is hear now and intends to take him home. He thinks of starting Monday. Sunday and all is well and a very nice and warm and pleasant here today, looks like spring here today. If you were here you would think it is the nicest place in the world. You wanted to know how much I would give you to come down hear two keep house? As you said I had better stay as I was getting so attached to the place I should prefer a Black House Keeper so to be in the basics and I could get them cheaper than I could transport you down here and then you would want to go home two or three times a year and now how much have you made this time and received that paper with some dried beef but did not get a paper with any sweat flag in it if I did. I must have dropped it when I opened the paper as you said you sent me a piece and you said it would be good for what ailed me. I would like to know how you know what could be good for me but I think I could tell what would do me good if I could get it but then never mind there is better days coming for this poor Scum somewhere. Oh how many times I have of the eve we was at Franks since you went there that time. Oh I don’t know as it would made any difference with my enlisting if you had told me that you would have been ready to have been married this fall for I don’t think I am in now another place but where I should be. The time I think will soon come that this war will close if Burnside keep on the ways that he has commenced and I hope he will.

E. W. Stacey

The soldier Erastus Stacey refers to as having died was 19-year old Lewis Smithers. He enlisted in August 1862 in Oswegatchie, New York as a private and was mustered into G Company of New York’s 142nd Infantry. Lewis died while at Upton’s Hill on December 28, 1862 from unknown causes (probably disease).

During the Civil War, more than 40 different Union Regiments were stationed at one time or another around Upton’s Hill. As a result, over 30,000 different Union servicemen were stationed there between 1862-1865. Several Union forts were arrayed around Upton’s Hill including Fort Ramsay, Fort Buffalo, and Fort Taylor. They were part of the system of Union forts guarding the Capital city against possible Confederate attack. They left behind countless artifacts, a few of which may be seen here. (All artifacts were unearthed with permission on or near Upton’s Hill)

Buttons from New York State Militia uniforms

.

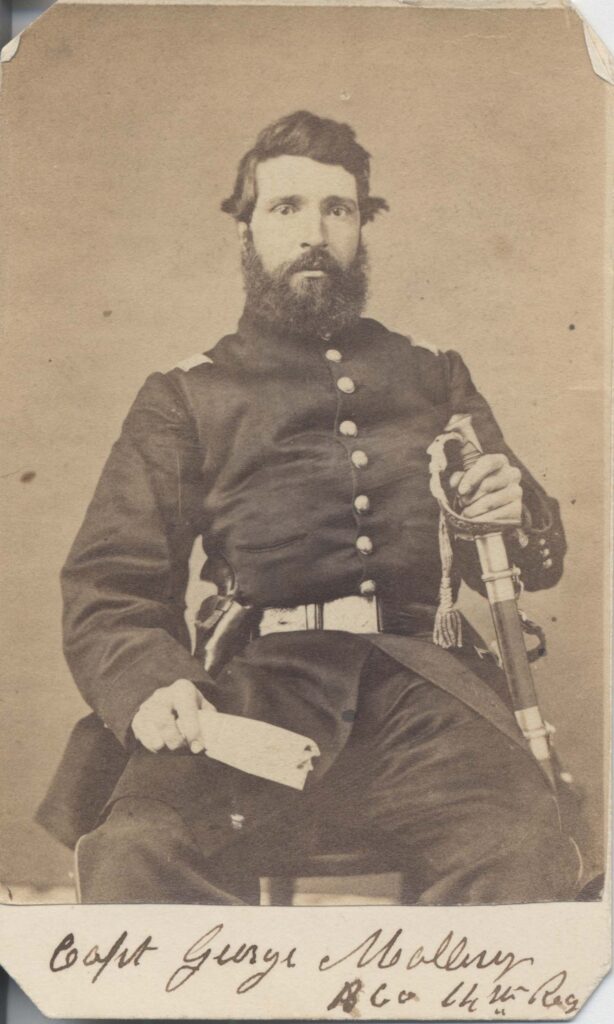

Captain George Mallory, Company B, 14th Regiment, New York State Militia had his photograph taken at an army photographic studio at Upton’s Hill. Such studios popped up near concentrations of men preparing for battle so that they could send their photograph to send to loved ones as a remembrance in case they were killed in battle. There were several in Alexandria County (now Arlington). Captain Mallory was killed in action on August 29, 1862 in the Battle of Groveton, Virginia. He was 34 years old.

1859 Indian Head penny found near Upton’s Hill. This worn penny was probably lost from a soldier’s pocket.

An example of an 1859 Indian Head penny in near mint condition.

A metal rivet, likely from a solder’s backpack

Civil War officer’s brass sash buckle

Mechanical pencil casing and lead pencil fragment

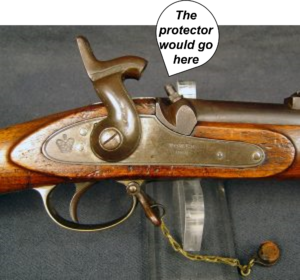

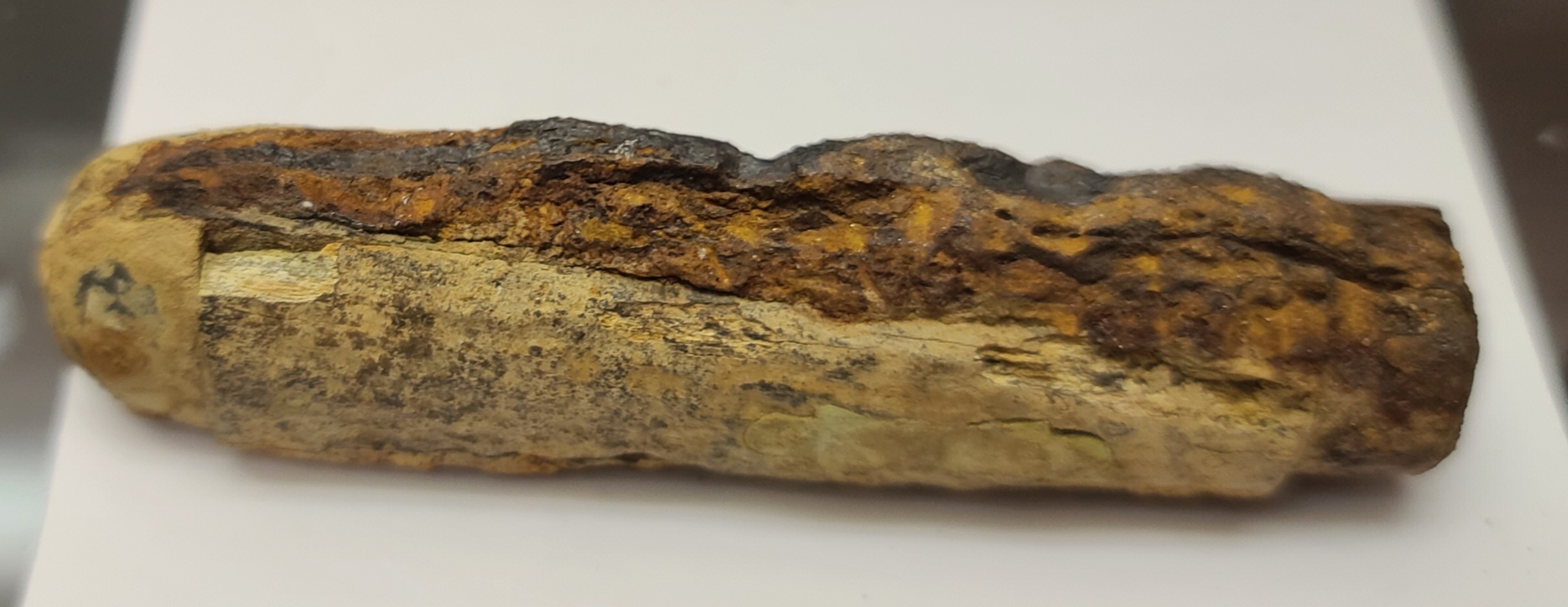

Handmade nipple protectors for rifle-muskets. The nipple protector, officially called a “cone,” was issued on many Enfield rifles imported during the Civil War. It was a lead cover placed over the “nipple” of the percussion musket to protect the nipple and hammer from damage if the rifle was accidentally fired. The cover prevented the hammer from coming down, meeting the percussion cap, and exploding the bullet through the barrel. Most were attached with a short chain to the trigger guard (see annotated image on the right) and were probably easily lost during military use or soldiers may have removed it themselves.

Soldier’s pocket knife

Glass shards found at Upton’s Hill, likely from the Civil War era from top: a piece of green bottle, ink bottle shard (center) and a piece of a pickle bottle (left).

Game piece carved by soldier from a Minié ball

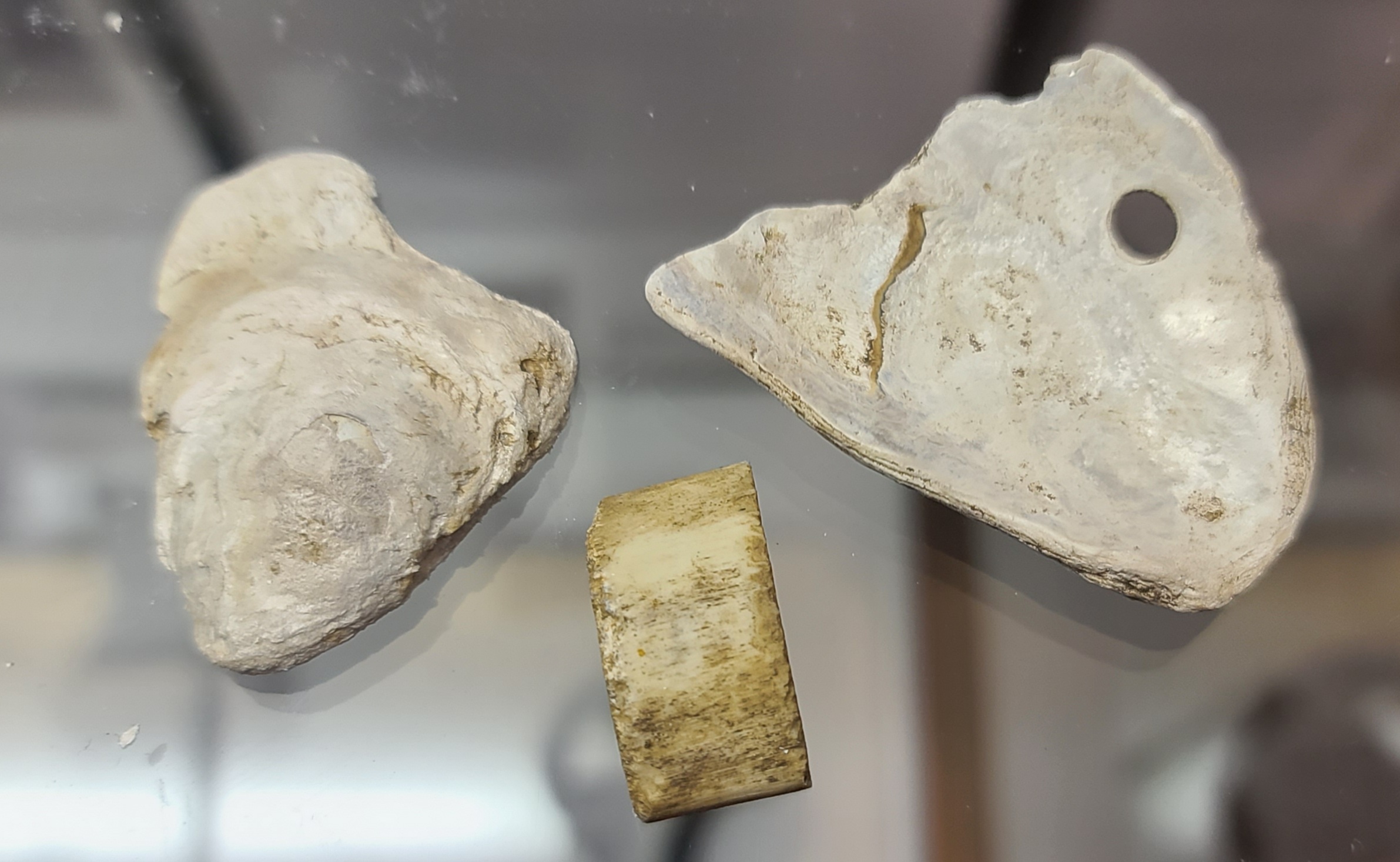

Oyster shells and butchered bone fragment from soldiers’ meals

Display Box (starting at the top)

• Two nails (top left and top right)

• Blue and white porcelain from dishware (top center)

• Three Minié balls and single shot

• Fork handle (horizontal in center)

• Pan handle (bottom left)

• Box handle (bottom center)

• Two pieces of camp lead: (bottom right) Soldiers on both sides of the Civil War were issued pre-packaged rounds wrapped in paper. These rounds included a charge of black powder and a Minié ball or round ball. When starting a campfire soldiers would often use one or two rounds to start their camp fires. The result was “camp lead” or small lumps of melted lead. Today, discovery of these small lumps of lead usually confirms the location of a camp.

To learn more about Upton’s Hill during the Civil War click on this video of an AHS hosted free public lecture: “Rediscovering Upton’s Hill History” by Peter Vaselopulos in 2021.

Turn of the Century

In 1898 Alvin Lothrop, co-founder of the Woodward and Lothrop department store chain bought the Febrey house at Upton’s Hill and used it as a summer and weekend retreat from his mansion in Washington, D.C. Lothrop is responsible for the construction of the Colonial Revival-style portion of the house designed by architect Victor Mindeleff, that Arlingtonians came to know atop the hill. After Lothrop’s death in 1912, the family continued to own it and installed a pool and bath house in 1934.

Alvin Lothrop (1847-1912)

The Lothrop house in the country, as depicted in the Washington newspapers of the time.

Pool, photo taken in 21st century

Bath house or cabana, photo taken in 21st century

World War II

During World War II, the Lothrop family leased the house to Trans World Airlines which was founded and owned by Howard Hughes, the eccentric real estate mogul and pilot. Hughes hosted parties there, entertaining movie stars, athletes, and Washington luminaries.

Actress Marian Marsh and Howard Hughes at a dinner party

Woman’s broach

An etched olive fork

Serving spoon

Padlock

Modern Era

By 1950, the house was empty and socialite, bachelor, and real estate developer Randall “Randy” Rouse (1917-2017) bought the house and 26 surrounding acres from the Lothrops. He kept nine acres for himself and developed much of the rest of the property into the Dominion Hills community.

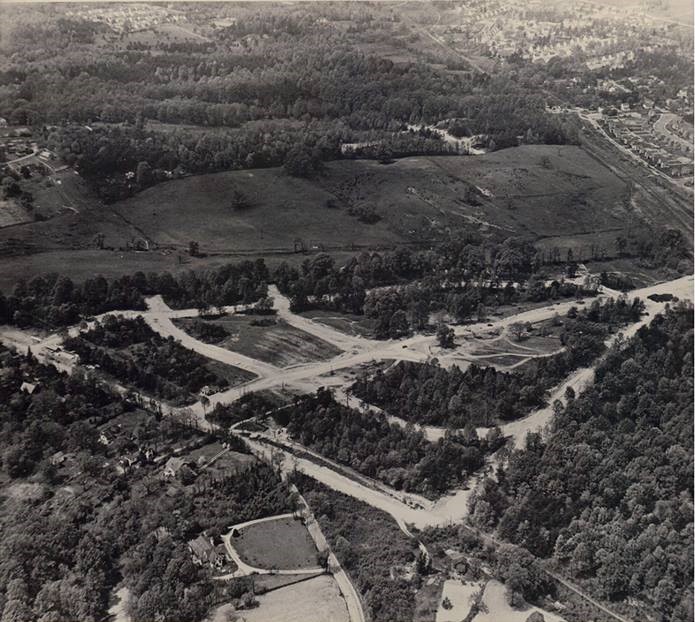

Aerial view of the Upton’s Hill area as Randall Rouse began developing the Dominion Hills neighborhood.

Randy Rouse with new bride, Audrey Meadows

A few years later, Rouse met and married actress Audrey Meadows, star of the Jackie Gleason sitcom The Honeymooners. The couple divorced but even after remarrying, Rouse kept the décor chosen by his first wife. Rouse died in 2017. The historic home was sold to developers by his estate and was destroyed in 2021.

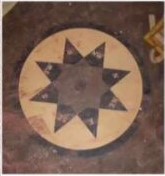

Tile floor design inside the house before demolition in April 2021.

The house, facing east (photo courtesy Center for Local History)

View from inside the house (Photo courtesy Peter Vaselopulos)

The house just before demolition. (Photo courtesy ArlNow)

The impressive house once symbolized the historic nature of the site and Arlington history surrounded the area in many layers around and below the site of the house. Through this exhibit, the Arlington Historical Society hopes to show the historic context of Upton’s Hill from top to bottom.

AHS is thankful to Peter Vaselopulos and all those who donated or loaned their personal artifacts of Upton’s Hill for this exhibit. All artifacts were unearthed with permission.