Horace Branson

Horace Branson was born to an enslaved woman, Julia Branson, around 1846. Records show that Julia gave birth to four other children, both older and younger than Horace: William, Mary Ann, James, and Frank. The family was enslaved by Smith Minor, who had a farm located along present-day Langston Boulevard, about where the Rivendell School currently stands.

Horace Branson was born to an enslaved woman, Julia Branson, around 1846. Records show that Julia gave birth to four other children, both older and younger than Horace: William, Mary Ann, James, and Frank. The family was enslaved by Smith Minor, who had a farm located along present-day Langston Boulevard, about where the Rivendell School currently stands.

After the Civil War started in 1861, Union troops built forts and encamped throughout Arlington (then part of Alexandria County). In the process, they seized crops and property from local farms. To escape the disorder, Smith Minor moved into the District of Columbia in September of that year, bringing along Horace, his mother and four siblings, and Moses Bennet, another enslaved man.

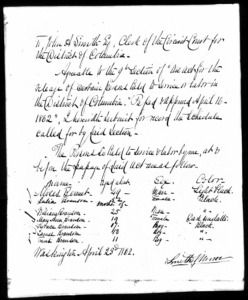

Horace, his family, and Bennet were all freed in 1862, when Congress passed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act. In April 1862, Smith Minor sought compensation for freeing the Bransons and Bennet, claiming $1200 for Horace alone. According to Minor’s petition, Horace was then 17 years old and 5 feet 10 inches tall. He was described as “a pretty good wagoner and fair farm hand.” A commission appointed by President Lincoln to oversee the petition and compensation process denied Smith’s claim. Only Union loyalists were eligible, and Minor had voted for secession in a local election in May 1861.

In the 1870s, Smith Minor made a reappearance in Horace’s life. Horace testified before the Southern Claims Commission in Minor’s attempt to gain compensation for property damage and loss caused by Union troops during the Civil War. Horace reported that the army took bricks from the property and used them to build cooking ovens. When the interviewer asked what ultimately happened to the bricks, Horace’s response gives a glimpse of his life during the war.

Q. I ask you what became of the bricks after they [the troops] left the camp and went away.

A. I could not tell you what became of them because I went away with the army then.

Q. You went off with the army?

A. Yes sir.

Q. You don’t pretend that you went with the Union Army, do you?

A. Of course I went with the Union Army. I was with Capt. Cole of the Union Army.

Records do not show in what capacity Horace went with the Union Army.

After the war, Horace made his life in Washington. On December 29, 1869, Horace married Catherine C. Fately in the District, and an 1870 Washington directory lists him as a waiter living on Ridge Street, Northwest.

The 1880 census shows Horace, described as a laborer, living in Washington, DC, with three daughters: Emma (age 8), Julia (age 5), and Estelle (age 2). No wife is listed, and the fate of his wife, Catherine, is unknown. On July 31, 1890, Horace marries again, to Delia Hazard, but by 1900 the census shows him living on Virginia Avenue with a wife named Cadiva. Horace, now 55 years old, is described as a laborer and barber. And he still has a houseful of daughters: Ruth (age 8), Elnora (age 6), and Henrigena (sp?, age 1). After 1900, Horace and his family disappear from the records.

—Heidi Fritschel