“Citizens at the Wilson High School waiting to vote in the national presidential election. The election started at 7:45 a.m., and a continuous stream of people, mostly men, came in. The women came later in the day.” Arlington County, November 7, 1944. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Arlington’s First Elections

According to historian C.B. Rose, people living in what is now Arlington would have been able to vote after early settlements were incorporated around 1645. Voting likely increased when the land of present-day Arlington was established as Fairfax County and received its own Court House in the town of Alexandria in 1752. At this point in time, all voting had to take place at a Court House, which limited eligible voters who lived far away from these buildings.

The first American elections were conducted by voice vote, or with paper ballots also known as “party tickets.” Unlike the “Australian” or “blanket ballots” that were used in the latter half of the 19th century, these early ballots only carried the name of candidates from a single party. These ballots would then be counted by local party and election officials.

In 1869, a change to the Constitution meant that “secret” ballots were now required and required voters to register prior to elections. A registrar was assigned for 1,000 voters along with an accompanying polling place – an early version of the precinct system.

Arlington citizens lined up to vote at fire stations in Arlington, 1944 (courtesy Library of Congress)

Many Americans have had to fight to get to vote.

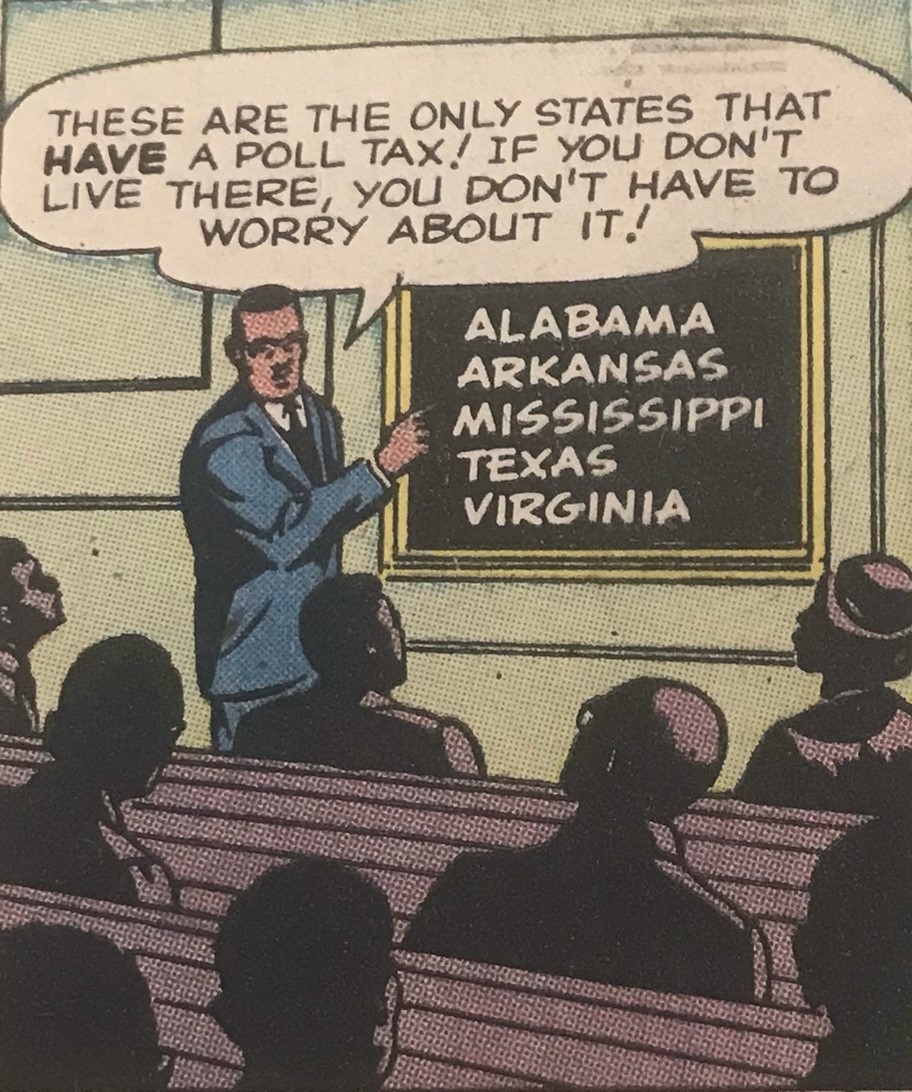

The 15th Constitutional Amendment adopted in 1870 granted all men regardless of race or color the right to vote. But by 1890 discriminatory practices were increasingly used to prevent blacks from exercising their right to vote, especially in the South.

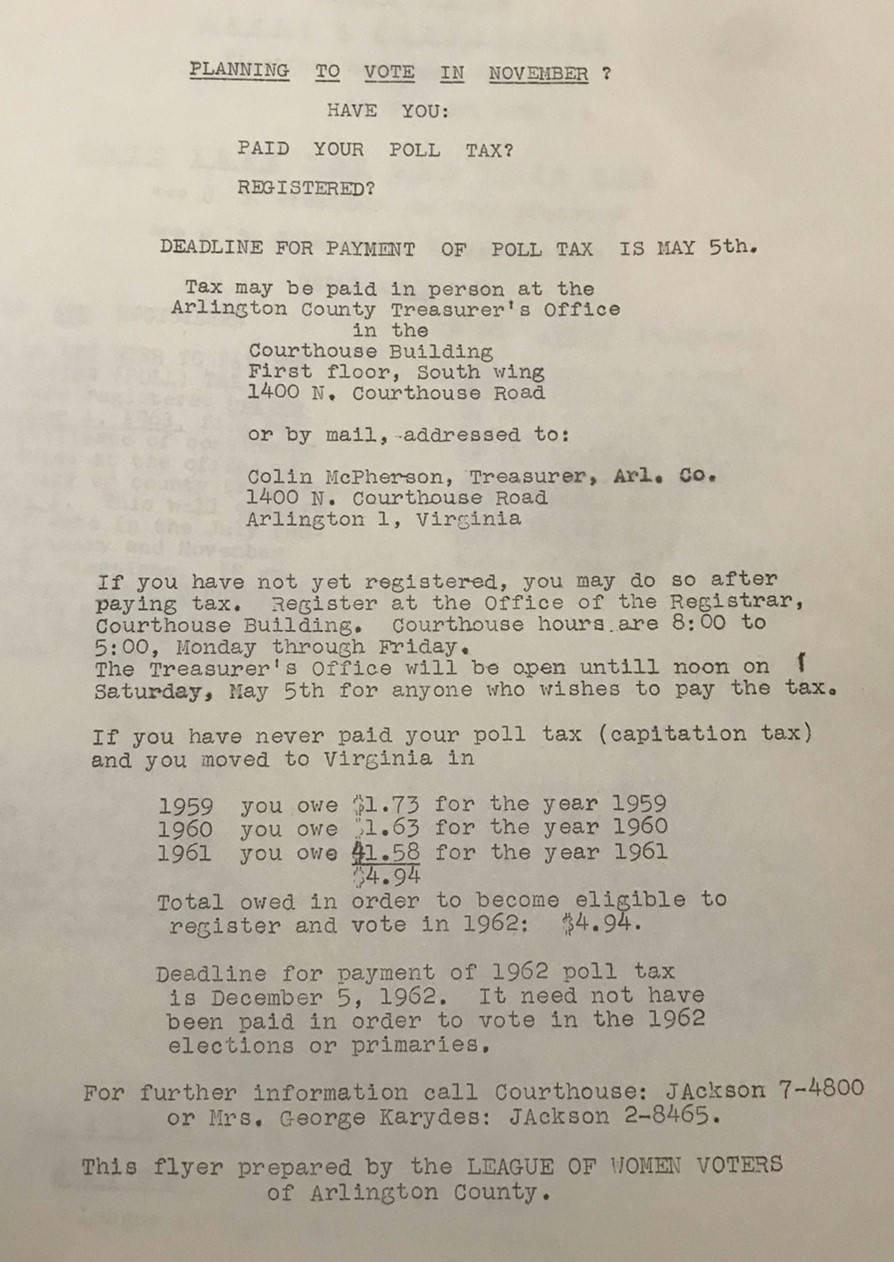

Virginia and several other southern states levied poll taxes as a legal means of keeping African Americans from voting. Poll taxes were essentially a voting fee that African Americans were required to pay before they could cast a ballot. The tax was accumulative, so voters could not skip a year and hope to vote the next unless they paid their back taxes.

Enshrined in the original 1902 Virginia constitution, the poll tax also disenfranchised poor white voters. A “Grandfather clause” allowed those whose fathers or grandfathers had been allowed to vote before the Civil War to avoid the poll tax, a loophole that did not apply to black voters.

(National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Voting Booklet, Courtesy Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library)

This poll tax flyer below was distributed in African American neighborhoods in Arlington by the League of Women Voters of Arlington County to let voters know about the poll tax before they went to the polls so they would know to pay them in advance. The fees seem tiny by today’s standards, but the average black worker took home just $9 a day in 1960, regardless of family size so these costs represented a large percentage of their income.

(Courtesy Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library)

The Twentieth-Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1964, bans the poll tax. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed other barriers such as “literacy tests” at the state and local levels if they denied any Americans the right to vote under the 15th Amendment.

The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage

Women were not always allowed to vote either. These women suffragists were in front of the White House protesting for the right to vote in 1917. A Constitutional Amendment passed in August of 1920 which allowed women to vote.

(Courtesy Library of Congress)

In these early elections, only a fraction of the population was permitted to vote, initially granting the right solely to propertied white men. Because of these limitations, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, women’s suffrage was a major reform issue nationwide.

“Votes for first time at 79. Arlington, VA, Oct. 15. This is Mrs. Lucy O’Leary of this town who will cast her first vote on November 3 at age 79, for Gov. Landon. She now lives on small government pension with the aid of a small garden.” Arlington County, October 15, 1936. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Gertrude Crocker was among those on the front lines fighting for women’s right to vote, and would later become a prominent Arlington citizen, owning and operating the Little Tea House. Crocker was among the “Silent Sentinels,” who, on January 10, 1917, participated in the first picket protest outside of the White House.

The 19th Amendment was adopted on August 18, 1920, after decades of advocacy. But after the milestone of women’s suffrage came another portion of the journey for equal voting rights for all. Though women had achieved the right to vote, large portions of the country’s non-white population were still disenfranchised.

Don’t Take This Important Right for Granted

Here’s why, from an NAACP voting booklet:

(Courtesy Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library)

Make Your Voice Heard: VOTE!

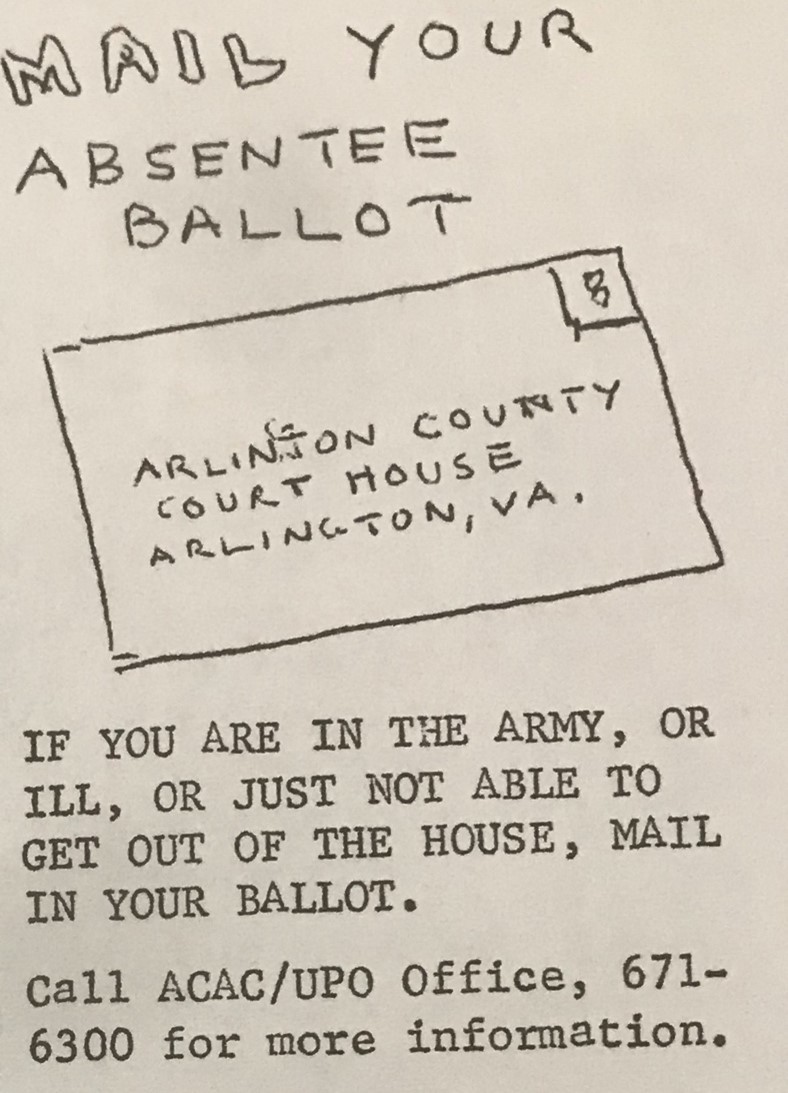

You can vote via the Postal Service:

“Green Valley News” clipping, ca. 1965 (Courtesy Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library)

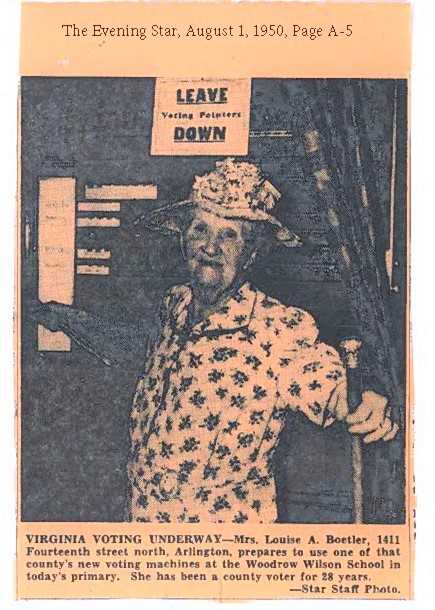

Or you can vote in person, like Mrs. Louise A. Boetler (shown below) did in 1950.

(“The Evening Star,” August 1, 1950, p. A-5)

The Modern Age of Voting

The last century has also seen technological developments in how we place our votes. From paper ballots, voting machines were introduced in the mid-20th century to modernize the voting process. Today, further developments, such as digital scanners introduced in 2015, continue to streamline how we vote and how our votes are counted.

Arlington County has also seen incredible growth from its humble electoral beginnings. The County now has 54 voter precincts and accompanying polling places. Almost every aspect of voting has changed in the centuries since the County’s beginnings: from who had the right to vote, to how voting was carried out.