The original circa 1742 John Ball house (left) with the 1800 Carlin family addition (right) of the Ball-Sellers House.

The Ball-Sellers House, at 5620 3rd Street South, is the oldest standing house in Arlington, Virginia, and the story that mostly has been told about this house and grounds is about the life and times of its white farmers and owners. Like everywhere throughout Arlington, however, stories of the enslaved workers and residents reside there, too. The history of the enslaved at the Ball-Sellers House and grounds reveals that the neighborhood in which the house is located (Glencarlyn, formerly Carlin Springs) and many landmarks in and around it—the former train station and post office, the current public library and elementary school, the community center Carlin Hall, and Carlin Springs Road—are named after a family that included slaveowners. At least two of the Carlin enslavers are buried in the cemetery next to the Glencarlyn library. Despite its history of slavery, the Glencarlyn neighborhood was developed in 1887 by an abolitionist, Samuel S. Burdett, a former Missouri congressman who served as commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, an organization of Union veterans. His partner in developing Glencarlyn was William W. Curtis, from Ohio, once a special correspondent of the New York Times covering some of the action in Virginia in the Civil War.

1st Era—The Ball Family: Yeoman farmer John Ball (1714–1766) received a land grant of 166 acres along Four Mile Run from Thomas Lord Fairfax in 1742, paying one shilling sterling for every fifty acres, and built the log house and lean-to that is part of today’s Ball-Sellers House. There, he lived with his wife Elizabeth Payne Ball (1716–1792) and five daughters, farming corn, wheat, and tobacco; keeping sheep, cows, pigs, geese, and bees; and running a grist mill on Four Mile Run. In 1748, John’s brother, Moses Ball (1717–1792), was granted 91 acres of land adjacent and south of John Ball’s land, near where the former urgent care facility stood (and the site of the “Moses Ball Spring”), where he built a house in 1755 and also farmed corn, wheat, and tobacco and kept sheep, cows, pigs, geese, and bees. There is no evidence that the Ball family enslaved people, though it is possible that they leased (rented) them from their neighbors to help with labor, as was common practice at the time, as many of the landowners around the Balls were enslavers.

2nd Era—1st Carlin Family: John Ball died in 1766; in 1772, William Carlin (1732–1820, buried in the Ball-Carlin cemetery in Glencarlyn) purchased the John Ball farm. John Ball’s widow Elizabeth Ball claimed her dower interest, which was one-third of the property, and continued living there—or in a different house on the property, where Kenmore Middle School is now. Carlin was an Alexandria tailor whose shop was located at King and Royal Streets (opened in the 1760s) and whose customers included George and Martha Washington, George Mason and his sons (including John Mason, one-time owner of Roosevelt Island, who began getting fitted by Carlin when he was 6 in 1772), John Parke Custis, as well as attorneys and tavernkeepers, merchants and tradesmen, indentured servants. His customers included many different kinds of enslaved people, such as grooms of the gentry. In fact, nearly 12 percent of Carlin’s known transactions for making or mending clothes for the enslaved were paid for by 37 percent of Carlin’s clients. Carlin also made house-calls to Mount Vernon to measure and cut clothes for George Washington’s enslaved staff.

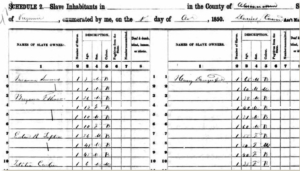

An 1850 census showing Letitia Carlin’s claim to one enslaved person.

Lost census records from 1790, 1800, and 1810 mean that there is no evidence that William Carlin enslaved people; however, his second wife and widow, Elizabeth Hall Carlin (died 1869, buried in the Ball-Carlin cemetery in Glencarlyn), and their children, enslaved at least two people. After he died in 1820, records show that he directed payment to a “negro hire” and “old negro Nancy to wait on Mrs. Carlin.” Similarly, in 1820, the census shows that Elizabeth Carlin enslaved two unnamed people, including a male born circa 1806; in 1830, the census shows she enslaved one woman over 55, believed to be Nancy (born circa 1775). Nancy likely served the Carlins by cooking, doing housework, and tending the kitchen garden. The 14-year-old boy likely farmed, provided animal care, ran errands, made household repairs, and aided Nancy. The 6-year-old likely tended animals, cleaned, and helped with serving and childcare.

When William Carlin died, his land (the original 166 acres, plus other land he purchased that added up to 191 acres—half of which was described as “well timbered” and half “in a pretty good state of cultivation,” with a “tolerable comfortable dwelling house, kitchen, and other out houses” and “an orchard of excellent fruit and a well of first rate water in the yard”) was split up among his three sons:

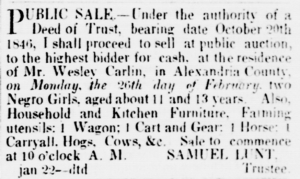

1. Wesley Carlin (1788-1875) inherited 34 acres of the Ball tract on the west side of Carlin Springs Road, and more land from another tract. Records show that in 1830, he was enslaving three people; in 1840, four people – a woman and three children. In 1846, an Alexandria paper advertised a public auction at his home to sell two children (an 11- and a 13-year-old girl). In 1850, he was enslaving a 16-year-old female, and in 1860 he was enslaving two girls, ages 5 and 7.

An 1846 ad from the Alexandria Gazette for the sale of two children at Wesley Carlin’s home.

2. James Harvey Carlin (1800-1846, buried in the Ball-Carlin cemetery in Glencarlyn) inherited 94 acres of the Ball tract known as the “mansion house tract” (referring to the BallSellers House), plus parts of another tract. Available records do not show that he enslaved people.

3. George Whitfield Carlin (1786-1843) inherited 63 acres of the Ball tract west of Carlin Springs Road. Available records do not show that he enslaved people. He sold his land in 1839 to William H. Torreyson, who would also come to own what is known in Arlington as the Reeves Farm in nearby Bluemont Park.

(No land was allocated to William Carlin’s daughters.)

3rd Era—2nd Carlin Family: Wesley Carlin’s daughter, Mary Carlin (1818-1905) bought a 40- acre parcel that included his home, which is now known as the Mary Carlin House at Carlin Springs Road and N. 1st Place. Upon his death in 1846, James Harvey Carlin’s deed was assigned to his widow, Letitia (“Littie”) Marcetta Skidmore Carlin (1797- 1866, buried in the Ball-Carlin cemetery in Glencarlyn) and their four children, John Edward Fletcher Carlin (1822-1900), William H.F. Carlin (1825-1901), Anne Eizabeth America Carlin (1828- 1892), and Andrew Wilson Franklin Carlin (1831-1885). Records show that in 1850, Letitia Margetta Skidmore Carlin was enslaving a 6-year-old “mulatto” boy (born circa 1844). She still lived in the Ball-Sellers House in the 1860s.

Reflections on Slavery at the Ball-Sellers House

Slavery was dehumanizing and brutal. It occured at the BallSellers House, in the Glencarlyn neighborhood, throughout Arlington County, and beyond. Historical records reflect the ugly truths of slavery, often describing enslaved people as property with only an age and a gender. Very few names can be found. Yet, the missing information cannot wipe out the existence of the unnamed, like the two boys enslaved by the Carlin family. Their presence has been noted; they are not forgotten. Recovering Nancy’s name may provide access to additional discoveries about her life. It also serves to humanize Nancy, to remind us that she was a real person who loved and dreamed and felt the pain of enslavement.

Prepared by Tim Aiken, Jessica Kaplan, Annette Benbow, Sue Eisenfeld, and Cindy Olson. Arlington Historical Society, October 2023

Sources:

Aiken, T. (2022). “Glencarlyn’s Unexplored Past.” Arlington Historical Magazine. Arlington Historical Society.

Backus, H. (1952). “Recollections of a Native-Born Glencarlynite,” In Glencarlyn Remembered: The First 100 Years. (1994, May). Glencarlyn Citizens Association. Egner, K.E. (2011) “’By Measures Taken of Men’: Clothing the Classes in William Carlin’s Alexandria.” Dissertations, Theses, and Master’s Projects. Paper 1539626659, College of William & Mary, retrieved from https:// scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5938&context=etd

“Farm for Sale.” (1836, August 24). Alexandria Gazette.

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Glencarlyn Historic District. (2008, August 1). U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/000-9704_Glencaryln_HD_2008_NR_final.pdf

Census, slave schedules, and other historical documents from Ancestry.com

Get Involved with “Memorializing the Enslaved in Arlington” Project

• Share your family story about slavery

• Volunteer as a researcher, writer, database inputter, and more

• Sponsor a “stumbling stone”

Contact Jessica Kaplan at ahsedlink@gmail.com