By Jacob Jordan

Before the Battle of Bull Run (July 18, 1861) in Manassas, the nation could not imagine the horrors of war. However, Arlington had a front row seat to the creation of the Army of the Potomac and a new type of hero.

The death of Colonel Ellsworth

In the early days of the American Civil War (1861-1865), bravery did not always come from where one expected. Military ranks and West Point training did not always guarantee valor and prowess on the field of battle. And sometimes, the courage of a soldier was strongest in a man who had never seen a military academy nor was in command of an army. While generals plotted, calculated, and hesitated, one young man, untested but unafraid, took a stand that shook a nation. His name was Elmer Ellsworth, and though history often forgets him, his courage and sacrifice was admired by many during the Civil War, even Lincoln himself.

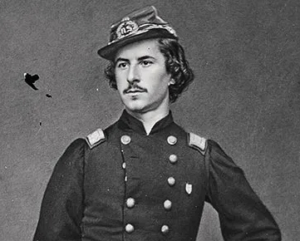

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth. 11th New York Regiment.

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth was not a soldier by training. Born in New York in 1837, and raised under a modest family, Ellsworth lacked the means to pursue training at his dream school of West Point, and instead studied to be a lawyer. Although he was relatively successful in his studies of law, Ellsworth’s fascination in military science and drill grew, and he would soon begin to attend drill competitions and reading manual after manual on military science, drill, and battle tactics. After immersing himself in the world of military for multiple years . Ellsworth became known in the Military community by drilling local militias around the nation including the Rockford Greys of Indiana. He later became renowned for organizing the Zouave Cadets, a flamboyant militia unit that dazzled crowds with its French-inspired uniforms and precise drills. Despite his self taught training and education, Ellsworth had made a name for himself.

Dazzling audiences with his Fire Zouaves as they toured the country, Ellsworth’s charisma and patriotism soon caught the attention of Abraham Lincoln. The two grew close, and by the time war broke out in 1861, Ellsworth had become not only a personal aide to the president but a symbol of the Union’s zeal. His dedication, optimism, and fierce loyalty to the cause made him stand out in Washington, even among seasoned officers.

Ellsworth’s moment came swiftly. On May 24, 1861, just one day after Virginia seceded from the Union, Union troops crossed the Potomac River into Arlington (then Alexandria county). Arlington, even in these earliest days of the war, had already become a contested zone. As both Union and Confederate forces vied for control of the heights overlooking the capital, the area witnessed early skirmishing and growing military activity. In response, the Union began heavily fortifying the region. Eventually, the Army of the Potomac, formed and headquartered nearby, would construct 22 forts and establish dozens of camps throughout Arlington, transforming it into the northern anchor of Washington’s defenses and a launch point for campaigns deeper into Virginia.

Early Confederate Civil War Flag known as “Stars and Bars”

In Alexandria, atop the Marshall House inn, flew a massive Confederate flag—so large that Lincoln could see it from the White House. To Ellsworth, it was more than a symbol of rebellion; it was a direct insult to the Union cause and had to be dealt with accordingly. Without hesitation, Ellsworth entered the inn with a small group of zouaves. He climbed the stairs himself, tore the flag down with his own hands, and began his descent. But waiting at the bottom of the roof’s stairwell was James Jackson, the innkeeper and a fervent secessionist. Jackson raised a shotgun and fired. Ellsworth was killed instantly, as he died bleeding upon both the flag and the hotel floor; he became the first Union officer to die in the Civil War.

News of his death spread quickly. Lincoln, devastated by the loss of his young friend, openly wept. Across the North, Ellsworth became a martyr. Though he had not died in a great battle, his sacrifice was noticed nonetheless. He had acted with courage and conviction, ultimately giving his life to remove a symbol of defiance to the Union Cause.

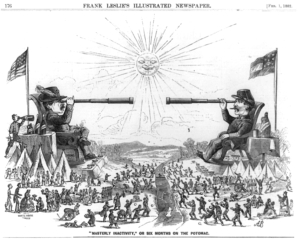

Union General George McClellan faces off against Confederate General P.T. Beauregard

Not long after, another Union officer would face a similar moment—but respond quite differently. George B. McClellan, often called the “Young Napoleon,” was everything Ellsworth was not. A West Point graduate, a Mexican-American War veteran, and a respected strategist, McClellan had all the credentials a great commander would have.

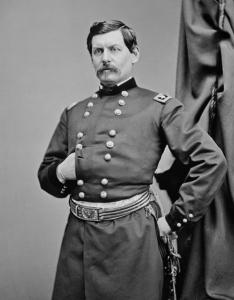

General George McClellan created the Army of the Potomac

When the Union suffered a humiliating defeat at First Bull Run, he was given command of the Army of the Potomac, composed of more than 100,000 men, he was hailed as the North’s best hope for turning the tide. But McClellan’s flaw was not lack of skill, it was his uncertainty.

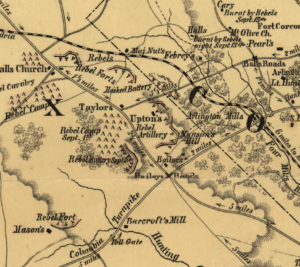

Early Civil War map of Northern Virginia showing the Confederate fortifications.

That fall, thousands of Confederate troops, led by General James Longstreet took up position on Munson’s Hill, a small rise in Northern Virginia clearly visible from the Capitol. From its summit flew another Confederate flag. To McClellan, the hill appeared heavily fortified, with imposing earthworks and rows of what looked like artillery. Convinced the enemy’s strength was overwhelming, he chose not to attack, letting the Confederate flag fly high above them. Weeks passed. The flag remained. McClellan continued to drill his troops and demand reinforcements from Lincoln. When Confederate forces finally withdrew, Union troops moved in—only to find that the “fort” had been a ruse. The cannons were mere logs painted black: decoys known as “Quaker guns.”

Union troops discover that the Confederate threat at Munson’s Hill was a ruse.

While the Confederates posed a modest military threat, McClellan perceived it to be much greater and made no attempt to challenge it. The contrast could not have been clearer. Ellsworth, with no formal training and no command, had torn down a rebel flag with his own hands and died for the cause he believed in, no hesitation, no fear. McClellan however, the distinguished general with every advantage, allowed a similar flag to wave unchecked, unwilling to test the strength of his enemy. One acted; the other waited. As the war dragged on, McClellan’s caution defined his legacy. He delayed attacks, overestimated Confederate numbers, and frustrated Lincoln with his endless requests and inaction. The president once famously said, “If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it.” Eventually, McClellan was relieved of command. He later ran against Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election, losing by a landslide.

Ellsworth never ran for president, nor lived to lead an army or fight a major battle. He died before earning a general’s star or wielding any real authority. Yet in a single act, he demonstrated more raw resolve than some of the most celebrated officers of his time, for this reason he will be remembered in history as valiant and brave, a hero among the Union.