Fugitive African Americans ford the Rappahannock River in the summer of 1862. (Source: Library of Congress)

Early in the Civil War, fighting between Northern and Southern armies drove thousands of African-Americans to seek freedom and refuge behind Federal lines. By late 1861, US troops had completed the construction of numerous fortifications in Arlington to defend Washington DC. While the forts had a military purpose, they also became beacons of freedom to thousands of refugees fleeing slavery. By 1862, their growing numbers forced the Federal government to address the problem of supporting the formerly enslaved and their emancipation status.

As US Army troops moved deeper into Virginia, military commanders had to make their own decisions regarding the status of African-American refugees. Some officers put escaped enslaved people to work for Union troops, while others returned them to plantation owners. Maryland slave owners, for example, were at odds with military authorities over escaped slaves in Washington and nearby areas. In the winter of 1862, some Maryland lawmakers wrote to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to complain.

There were no policies in place to deal with fugitive slaves until summer 1861, when Union Maj. General Benjamin Butler, at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, refused to send escaped slaves back to their owners. He classified the escaping slaves as contraband of war and ordered that they not be returned. Because of Butler’s actions, a federal policy called the “Confiscation Act” was enacted on August 6, 1861 — declaring fugitive slaves to be “contraband of war” and granting them freedom. At the start of the war, Lincoln was concerned about the border states and keeping them in the Union. But he was under significant political pressure to address the legal status of the formerly enslaved. The Confiscation Act was the start of a shift in policy that eventually led to the Emancipation Proclamation.

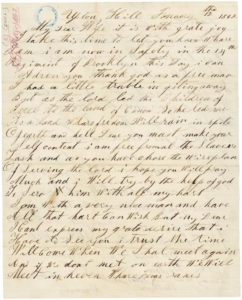

In early January of 1862, fleeing slavery in Maryland, John Boston found refuge with the 14th Brooklyn, a New York regiment encamped at Upton Hill. Early war photographs show dozens of camp scenes with Federal soldiers and the formerly enslaved. Befriended by the soldiers of the 14th Brooklyn, John most likely was hired to help out at the camp. John wrote a letter to his wife and children, who remained in Maryland. It is not clear if he wrote the letter himself or had assistance. But at the moment of celebrating his freedom, his highest hope and aspiration was to be reunited with his family.

In early January of 1862, fleeing slavery in Maryland, John Boston found refuge with the 14th Brooklyn, a New York regiment encamped at Upton Hill. Early war photographs show dozens of camp scenes with Federal soldiers and the formerly enslaved. Befriended by the soldiers of the 14th Brooklyn, John most likely was hired to help out at the camp. John wrote a letter to his wife and children, who remained in Maryland. It is not clear if he wrote the letter himself or had assistance. But at the moment of celebrating his freedom, his highest hope and aspiration was to be reunited with his family.

“My Dear Wife, it is with great joy I take this time to let you know where I am. I am now in the safety of the 14th Regiment of Brooklyn. Today, I can address you, thank God, as a free man. I had a little trouble in getting away, but as the lord led the Children of Israel to the land of Canon, so he led me to a land where freedom will rain despite earth and hell. Dear you must make yourself content, I am free from all the Slavers’ Lash . . . I am with a very nice man and have all that the heart can wish. But My Dear, I can’t express my great desire to see you. I trust the time Will Come When We shall meet again, and if we don’t meet on earth, We Will Meet in heaven, where Jesus reigns. . .”

There is no evidence that Elizabeth Boston ever received this letter. It was intercepted and eventually forwarded to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton by Major General George B. McClellan, providing evidence to the War Department and Lincoln administration of the refugee issue.

John Boston’s letter is a rare voice during a time when the contraband issue created confusion over the status of former slaves and those who were still legally enslaved. Lincoln initially prioritized preserving the Union and feared alienating the border states by directly addressing slavery. It is believed that the Boston letter had some impact on President Abraham Lincoln’s decision to sign a bill ending slavery in the District of Columbia on April 16, 1862,. This law’s passage occurred eight months before he issued his Emancipation Proclamation. The act brought to a conclusion decades of agitation aimed at ending what antislavery advocates called “the national shame” of slavery in the nation’s capital. It provided for immediate emancipation, compensation to former owners loyal to the Union of up to $300 for each freed slave, voluntary colonization of former slaves to locations outside the United States, and payments of up to $100 for each person choosing emigration. Almost one year later, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that slaves within the Confederacy were free.

The challenges of caring for these contrabands grew as their numbers increased. Northern aid and religious groups provided necessities like clothing and sent teachers to educate the former slaves, but overall, the primary responsibility for the contrabands remained with the Federal Government.

Gen. James S. Wadsworth, from Geneseo, New York, commanded the Military District of Washington from March 1862 to September 1862, facing the difficult task of managing the influx of contrabands. As the former regimental commander of the 14th Brooklyn during the time of John Boston’s letter, he was familiar with the problem.

Soon, thousands of freed slaves were permitted to settle in the Washington, D.C., area, including Arlington. These makeshift settlements, often built near Federal fortifications and camps, became Contraband camps; the most well-known was called Freedman’s Village. But their true legacy was the impact these camps had on President Abraham Lincoln.

Nearly a year later, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that enslaved persons within the Confederacy were free. Following this, the United States Colored Troops (USCT) were established on May 22, 1863, when the War Department issued General Order No. 143, creating the Bureau of Colored Troops. In Arlington, Camp Casey served as a recruitment and training center for several USCT regiments, including the 23rd USCT, which was the first Black regiment to fight against Robert E. Lee’s forces.

For more information: