Lewis Howard lived the first half of his life enslaved and the second half of his life free. He was born in 1834. His exact place of birth is unknown, but Alexander Hunter enslaved him at his plantation, known as Abingdon, located on what is now Reagan National Airport. Built in the 1740s by Gerard Alexander, Abingdon plantation covered 6,000-acre plantation along the Potomac River and was one of the largest places if enslavement in Arlington.*

Abingdon, ca. 1900

The 1840 census does not list Lewis Howard under Alexander Hunter. He is described by name in the 1850 probate inventory for Hunter, which named 22 enslaved people, ages 2 to 70 years, living in 5 or 6 cabins. He is enumerated by age and gender in the 1850 (age 16) and 1860 (age 26) Slave Schedules under his next owner, Bushrod W. Hunter, brother of Alexander Hunter.

It is likely that Lewis was involved in agricultural labor—tilling ground, planting seeds, cultivating and harvesting crops. Typical crops grown in the area along the Potomac River included clover, flax, oats, barley, corn, and potatoes. The 1861 diary of Bushrod W. Hunter documents Lewis as a wagon driver hauling rails and posts for fence repair. He may have transported Hunter’s produce to the markets in the District of Columbia and Alexandria City.

Lewis might also have been engaged in the care and feeding of the animals, who were raised for food and for hauling plows and wagons. Animals typically raised in the region included cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens. According to the 1850 inventory of Alexander Hunter’s estate, he maintained five cows, four bulls, at least six calves, two carriage horses, two sows, and 27 hogs.

When the Civil War began, life at Abingdon changed for both owners and enslaved. In 1861, B. W. Hunter and his son Alexander Hunter (2nd) left the plantation to join the Confederate Army. In 1862, the enslaved people of the plantation, including Lewis, were relocated to Washington, D.C., and the New Jersey Division of the Union Army occupied the plantation.

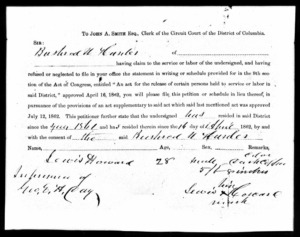

Residing in D.C. provided Lewis the opportunity to seek his freedom. On April 16, 1862, President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, which outlawed slavery in the District of Columbia nine months before the Emancipation Proclamation. Enslavers were reimbursed for their lost property if they could prove ownership and loyalty to the Union. B. W. Hunter did not apply for compensation. An amendment to the original act allowed formerly enslaved people to petition for compensation if their former enslavers had not done so. Lewis took advantage of the act by filing his own petition. The Rev. Julius C. Smith was noted as a witness on Lewis’s manumission record. He was 28 at the time of his emancipation.

Howard’s District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act Petition, 1862

In 1863, he was drafted into the Union Army, where he likely served in a Black regiment until the war ended in 1865. His draft record shows him as a laborer from Virginia. There are no records regarding where he served during the war.

Lewis remained in the District of Columbia after the war. He married a woman named Caroline. The 1880 census lists Lewis (age 46), his wife Caroline (age 45) and five children: John Francis (age 18) Leonard (age15), Carrie (age 12), Mary L. (age 10), and James E. (age 8). Martha (age 27) is included in the census as a household member. She might have been the oldest child or perhaps another relative.

In the census, Lewis and son John Francis were both listed as waiters. Caroline and Martha were listed as housekeepers. Carrie and Mary were noted as schoolchildren.

An 1870 and an 1887 city directory show Lewis residing on 13th and 14th streets in northwest D.C. and give his occupation as porter. His occupation is again described as a porter in an 1871 Freedman’s Bank record, which notes Caroline as his wife.

A marriage record from May 23, 1895 shows Lewis, at age 61, marrying Margaret Bowes. He died one year later on February 22, 1896.

*Abingdon house was destroyed in a fire in 1930. The site today is located between two parking garages at Reagan National Airport. It contains indoor and outdoor displays that commemorate the plantation’s history.

References: Thomas A. Foster, “’No Perfect Archive’: Recovering Histories of the Enslaved People at Abingdon Plantation,” The Journal of the Civil War Era, Volume 12, Number 4, December 2022, pp. 448-472 (Article)