Preservation

The Arlington Historical Society has a preservation education program for homeowners, real estate agents, and home builders. The program provides resources for all and a starting place for Arlingtonians to begin educating themselves on what preservation can mean to them.

As part of the effort to improve preservation of historic properties, the Arlington Historical Society (AHS) has appealed to scores of area homeowners and dozens of home-builders and real estate agents to consider preservation instead of tearing down.

“The demolition of several valuable properties including the historic Febrey-Lothrop house at 6407 Wilson Boulevard (shown at right) and the ‘Memory House’ at 6404 Washington Boulevard (below right), are key examples of beloved properties that fell to the wrecking ball without sufficient consideration, in our view, of creative alternatives,” the letter says. “We believe the best way to preserve more properties that reflect Arlington’s heritage is through education and negotiations that honor the interests of all parties.”

6407 Wilson Boulevard (shown at right) and the ‘Memory House’ at 6404 Washington Boulevard (below right), are key examples of beloved properties that fell to the wrecking ball without sufficient consideration, in our view, of creative alternatives,” the letter says. “We believe the best way to preserve more properties that reflect Arlington’s heritage is through education and negotiations that honor the interests of all parties.”

Acknowledging that the county is changing and expressing respect for “by-right ownership and the free-market considerations that go into home sales and improvements,” the Arlington Historical Society asks that owners, builders, and real estate agents conduct research on their properties before rushing to a tear-down option. “We feel that Arlington’s government, residents, and businesses could do more to preserve properties that represent either notable personages, events, or architectural styles,” the letter said.

Although AHS cannot offer official advice as to whether a given property is historic, it can assist in explorations of alternatives to demolition such as a historically minded buyer or an architect who could design a partial renovation.

AHS invites residents who have questions on the historic importance of any residential or commercial property to contact AHS via email: info@arlingtonhistoricalsociety.org or contact Arlington County’s Historic Preservation Program office at 703-228-3831.

A Committed Historic House Owner Who Worked with AHS

(June 2023, by Charlie Clark)

Preserving heritage homes requires owners who possess both investment capital and a principled commitment. That’s why the Arlington Historical Society was pleased this April when we were contacted by Amy Harasz, a real estate executive who had some exciting personal news.

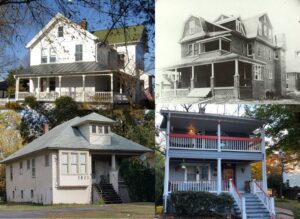

While jogging near Westover one morning in late 2021, she noticed a for-sale sign on a stunning green-and-mustard-painted wooden Victorian home at 1506 N. Nicholas St. Though she already owned a place in Dominion Hills, she was won over by this colorful two-story, three-bedroom gem with a tower, terra cotta sashes, fish-scale shingles and stained-glass windows. It was built in the 1892 in a neighborhood then called Fosteria (now Highland Park).

“I fell in love,” she said. “They just don’t make them like this anymore.” Coming up with the $1.195 million, she bought it from John and Anne Sullivan—who’d enjoyed it for 50 years. And they gave her artifacts, old photos, and news articles detailing the property’s story.

The home was designed by architect Barney Noland on the 11,600 sq. ft. lot. He also built a home for his newlywed daughter across the street, and when the Sullivans arrived in 1972, they received some furnishings from her estate, according to a November 13, 1983, Washington Post article by Linda Wheeler. Anna Dale Sullivan was a colorist and author of a regional book on home preservation. She had experienced the same instant love for the home as Amy Harasz. The exception being that when Sullivan knocked on the door in 1972, there was no for-sale sign–she just happened to inquire during an impending divorce!

Harasz has proceeded with a rehabilitation, though delivery of building materials and new appliances were delayed by the pandemic. “I wanted to retain its character, but make it modern, more functional,” such as opening up the space between the kitchen and dining area, she said while giving a tour among loose electrical wires and busy workmen. She is keeping many of the stained-glass windows, stair bannisters, built-in bookshelves and crown molding, as well as the tile in the library. But she’s adding French doors on the ground level, replacing a staircase and redividing the upstairs to enlarge the master bedroom. She’s adding modern kitchen cabinets and a mud room. And the cellar and foundation—in the old days merely a slab—had to be seriously and expensively waterproofed. She added a new powder room (when the house was built, the folks used an outhouse). The fireplaces in the living room and library are being converted to gas. And she replaced nine old doors, but sought places for some originals. The unfinished attic (where she found evidence of a past fire) is being outfitted with heating and air conditioning. “The engineering and permitting” have gone smoothly with the county, Harasz said. In the walls, crews found artifacts such as a ceramic vinegar bottle, a dinner plate, and an inkwell.

Out front, the circular brass (non-electric) doorbell has an old-fashioned feel, and an old bird house in the yard mimics the home’s design. “I love the idea of breathing life into forgotten homes,” she tells her clients.

When Harasz approached the Arlington Historical Society, she offered seven original doors, three stained-glass windows, and a corner cabinet that was built with the home. (We accepted the windows).) After 18 months and a crew working six days a week, the project was completed in the summer of 2023. She, her Westover neighbors and, indeed, all of Arlington, are better for it.