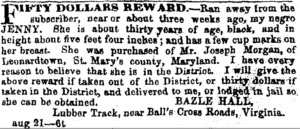

Observers reported that Bazil Hall and his wife, Elizabeth, were particularly cruel slaveowners. At least once, Jenny ran away from the Hall plantation. In August 1852, Hall placed an ad in a Maryland newspaper that read:

FIFTY DOLLARS REWARD—Ran away from the subscriber, near or about three weeks ago, my negro JENNY. She is about thirty years of age, black, and in height about five feet four inches; and has a few cup marks on her breast. She was purchased of Mr. Joseph Morgan, of Leonardtown, St. Mary’s county, Maryland. I have every reason to believe that she is in the District. I will give the above reward if taken out of the District, or thirty dollars if taken in the District, and delivered to me, or lodged in jail so she can be obtained.

Jenny was evidently returned to Hall’s plantation, though it is unclear how.

In 1857, an altercation between Jenny and Elizabeth Hall escalated into violence. Records show that on December 13, Jenny pushed Elizabeth Hall into a fire, fatally injuring her. As Elizabeth lay dying, the local justice of the peace collected her deposition, which was used in Jenny’s trial and reproduced in full on the front page of the Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser newspaper.

According to Elizabeth’s account, on the morning of December 13, she had asked Jenny to go to the nearby spring, but Jenny had sent another enslaved woman instead. According to Elizabeth, “I asked her why she had sent her to the spring contrary to my orders? She gave me some of her insolence, and I slapped her in the mouth.” After a further dispute about the burning of some wood in the fireplace, Elizabeth said, “She then caught me and put my head between her knees, and pushed me in the fire.” The deposition then described a struggle between the two women that lasted until others on the property arrived and intervened. Elizabeth died later that night. The newspaper did not provide any account of the incident from Jenny, beyond saying that she “stoutly denies that she committed the murder.”

A few weeks later, on January 5, 1858, Jenny was convicted of murder, and on February 26 she was executed by hanging. Years later, an 1886 memoir by John Henry Brown, who had known the Halls in San Francisco, cited Elizabeth Hall’s father about his daughter’s treatment of Jenny:

Mr. Winner told me that Mrs. Hall treated the colored woman brutally; and the woman, tired of her treatment, and determined to have revenge, one day put Mrs. Hall’s feet into the fire, and held them there until she was burned to death.

After Jenny’s death, her four sons—James Clark, William Farr, John Lewis Farr, and Joseph Farr—remained on the plantation with Bazil Hall.

When the Civil War broke out, Hall fled his property for Washington, DC, taking the boys with him. Skirmishes and marauding by the Union and Confederate Armies left Hall’s property in a shambles. His large house, as well as outbuildings and barns, were burned. The soldiers cut down his trees, destroyed fences, cut crops and hay, and took his livestock and farming equipment.

After the war, Bazil Hall returned to his plantation, and the four boys lived there as well. In 1866 James Clark was 14 years old, William Farr was 11 years old, John Lewis Farr was 10 years old, and Joseph Farr was 8 years old. James and John Lewis did farm labor, and William served as a cook. Observers reported that Hall provided them with no education and often beat them.

In March 1866, Hall was charged with mistreating the four boys, on two counts: (1) assault and battery and threatening to kill “colored persons” in his employ and (2) inhuman treatment of “colored persons”—that is, withholding pay and proper food and clothing and using the boys as slaves.

In proceedings before a special military Provost Court established to hear claims involving African Americans, the boys were represented by Joseph R. Johnson, a missionary with the Freedmen’s Bureau. Johnson testified, “To my mind, the proof is ample, that, since April 7th, 1864, B. Hall did treat as slaves, the four boys.” (April 7, 1864, marks the date when the Unionist government of Virginia abolished slavery in the parts of the state that remained loyal to the Union.)

According to the testimony in court, on March 10, Hall had beat John Lewis. A witness said that Hall whipped the boy and “bucked” him. “Bucking” was a form of beating in which the victim would sit with knees bent, and the hands would be tied and brought down over the knees until the chin rested on the knees. A stick would be passed over the elbows and below the crook of the knees, immobilizing the victim, who was then whipped.

John Lewis Farr testified:

I left Mr. Hall’s Sunday before last. I left him because he whipped me. He bucked me and whipped me and whipped me with a strap. He whipped me Friday before I left. It was at his stable he pulled my breeches down. I cried, Please Master don’t kill me. It is not the only time Mr. Hall whipt me. He whipt me a heap of times.

His brother William testified:

He has bucked me a heap of times. . . The last time he bucked me he whipped me with a wagon whip, this was because I staid too long at the spring… He has bucked us all. . . People has told me I was free but Mr. Hall never told me so.

The night John Lewis fled, Hall went looking for him, entering the homes of African Americans in the neighborhood. One witness said:

He had his gun with him. It was about dusk. We were sitting at the table eating supper and had a candle lighted. He said that he would shoot anyone if he knew that they was harboring him.

Johnson, the missionary, noted that since emancipation the boys had worked for Hall without pay. Hall had also misled Alfred Farr, the boys’ father, by telling him he needed written notification from Congress to gain custody of the boys.

The Provost judge, Captain Paul R. Hambrick, found Hall guilty on both counts. He fined Hall $50, saying he was showing leniency because of Hall’s general treatment of African Americans (he had, among other things, donated land for a Freedmen’s school) and his support for the Union.

Hall never paid the fine. In May 1866, Hall’s lawyer wrote to President Andrew Johnson to argue that the Provost Court had no jurisdiction in the case. President Johnson ordered the military to drop the case and turn it over to civilian authorities, and there it died. After this episode, nothing more is known about the fate of the four boys.